- January 28, 2020

- Machiel Lamers

Learning across disciplines

The guide is carefully steering the dinghy towards the mangrove-covered shore. His assistant stands in the front on the lookout. The last few meters he carefully pushes it towards the mangrove using his pole while avoiding the corals. We are doing some water quality measurements with the students at different distances and depths from the resorts, homestays, villages and mangroves in several places on our trip. We want to see if there are different levels of nutrient or sediment outflow near human activities in the region. This may help inform our joint project proposal.

Abracadabra

A key objective of our expedition is to learn across different disciplines about the impacts of tourism in Raja Ampat. I am an environmental sociologist. Seeing researchers from other disciplines in action helps. In preparing for the expedition I read all the protocols and listened to the introductory talks, but some of the terms used remained ‘abracadabra’. At the recap on the first evening of our expedition, after having snorkeled above the dive team assessing the state of the reef at 5 meters depth, I proudly claimed: “Now I know what a transect is!”.

At the same time the natural scientists also joined us ashore on our visits to villages conducting semi-structured interviews with our Indonesian colleagues. The aim was to explore the perspective of villagers on the impacts of tourism development both above and below the water. On one of these occasions Pa Ery, an Indonesian PhD researcher, skillfully gains trust by moving from courtesy questions to more critical issues. As Erik, a marine biologist and underwater photography expert, observes the interview he whispers in my direction: “This way an hour can pass easily.”

Organic samples

Back to the mangrove. One of the students asks: “Depth?” “0.9 meters” replies Eva, a behavioural economist. Cyano? 3.1. Total? 3.3. Turbity? 0.0. It is my task to write everything down on a score sheet. Some of the measurements require nothing more than sticking an instrument into the sea and noting down the result. For others, there is a strict protocol of multiple steps. For example, for most biological samples the processing that needs to be done on the ship is lengthy and detailed.

Organic samples need to be systematically labelled, carefully inserted into an aluminium foil pocket, dried in a rice cooker and brought back to the lab in Wageningen.

It is encouraging to see the dedication and work ethic of everybody on board, working non-stop for hours in order to secure the data. For example organic samples need to be systematically labelled in terms of species name, day and place, carefully inserted into an aluminium foil pocket, dried in a rice cooker and brought back to the lab in Wageningen to be tested by the students on isotopes. This can reveal the type and level of pollutants that the organism has been exposed to. Potentially powerful results, also for social scientists, which we can use in our interviews or participatory approaches with key decision makers.

- January 27, 2020

- Erik Horstman

Jack & Jelly

Imagine jumping into a lake full of jellyfish, sounds crazy right? That’s what we got to do today! Lisa got to show us one of ‘her’ Jellyfish lakes, Lake Lenmakana. This lake is a marine lake, which means it is a brackish lake that is isolated from the surrounding sea. These marine lakes are home to a unique stingless jellyfish, the Mastigias Papua, whose evolution took a different course after it got trapped in these lakes.

Thousands of jellyfish

Lenmakana is a little island formed by a ring of steep mountains with the lake right in its middle. Hence, after we got dropped off by the crew from our Liveaboard, we started a steep ascent onto the mountain ridge surrounding the lake. Navigating our way up between the sharp and irregular edges of the limestone, we got some amazing views of the sprinkle of islands in the surrounding ocean. Nothing as breathtaking as the views that followed after we crossed the ridge though… thousands and thousands of jellyfish had gathered where the sun lit up the lake.

After a quick descent, we plunged into the lake and submerged ourselves in this mesmerizing environment. There were jellyfish all around and they didn’t seem afraid of us at all. Their uncoordinated movement made them bump right into us, even on our faces! Such a weird sensation to have these mushy jellyfish bumping into you. Good thing they were stingless.

Lonely Jack

However, not all inhabitants of the lake were that friendly. We spotted a huge lonely Jack. These fish don’t really belong in the marine lakes, but somehow it ended up in this one. Probably not to its own liking, as there is only limited food for Jacks in these lakes. And so we noticed… Later that afternoon the students were doing their experiments when, attracted by the smell of canned tuna, Jack had a little go at them. No blood was shed, but suddenly Jack didn’t look that innocent anymore.

Surprisingly, the look of all these appetizing (sarcasm!) jellies had made some of our crew hungry for jelly. We said farewell to the jellyfish and climbed off the island to rush back to our liveaboard for yet another copious meal. The crew of the Temukira is pampering us very much. Good thing we got some more exercise in the afternoon while exploring the waters and village of Harapan Jaya. This is one of the many little coastal townships throughout Misool combining traditional fishing trade and tourism.

Back to the village

As it was a Sunday, all the kids were out on the jetty, curiously observing us while we were curiously observing them. Later in the afternoon a few members of our expedition made landfall to find out how these villagers go about their change of trade into tourism and the consequences of that. Interesting observations that will be addressed in our next blog.

And Jack? He had another go at the students the day after and probably lives grumpily ever after in his lake full of inedible jellies.

- Ingrid van de Leemput

- January 22, 2020

Exclusive eco-tourism?

Today we arrived in Misool after sailing through the night. We woke up with a stunning sunrise, and a magnificent view on many green islands, randomly distributed in the ocean. In comparison with Dampier we see much fewer liveaboards and no homestays. However, we turn out to be anchored in front of a beautiful resort, which colors and materials blend in with the landscape. Our expedition leader quickly tells the captain that the view on our tourist boat will probably not be appreciated by the visitors of the resort, so we sail to a location just out of sight.

When we arrive on shore we are welcomed by the owners of the resort. It is a highly exclusive eco-resort. Already from the first sight, it is clear that the owners are very dedicated to minimize the impact on the ecosystem. I’m impressed. Next to each hut is a little garden of five by five meters with green plants. These are wastewater gardens that are supposed to take up the nutrients of toilet-visits, preventing pollution of the home reef. There are solar panels, and solar boilers, that provide the resort with electricity and hot water.

The bay in front of the reef is full of sea turtles that don’t seem to mind our presence.

The care for the reefs stretches out towards the sea around the islands: there is a well-functioning regime to regulate the number of liveaboards and divers on popular dive sites.

Sharks swim around quietly again

The owners know very well how unique these reefs are. So they do everything to share their sustainable vision on tourism in Raja Ampat with local and regional policy makers. Not even twenty years ago shark finning and blast-fishing (fishing with dynamite) were common practice in this area. At this moment, the black-tip reef sharks are swimming quietly close to the jetty. And the bay in front of the reef is full of sea turtles that don’t seem to mind our presence. While snorkeling a bit further from the resort I notice the high coral cover, very few algae, and the presence of many fish.

Regulating tourism

After our visit, I keep thinking about how this success relates to the rest of Raja Ampat. Only exclusive eco-resorts seem no option. For the majority of tourists this area will be completely out of reach. Is this bad? Does everybody have the ‘right’ to be here or not? I discuss with the social scientists on our trip if there are other possibilities besides raising prices to regulate the flow of tourists. I could think about a lottery or a waiting list. However, Indonesia wants to have a fast-growing economy, and one of the focus points nowadays is tourism in Raja Ampat.

The owners of the resort suggested to define different zone, ranging from completely closed areas to regulated areas to freely accessible areas. I also think about ways to apply the local regulation system, Sasi, to tourism. With Sasi some months of the year tourists are allowed in the area, and after that the system gets some time to recover. All our great top-down ideas to lower the pressure on the system seem quite simple. But what about the local and political stakes, and involvement?

Social challenge

In my opinion, the real challenge of this expedition is not ecological, but social. What excites the local people? How can be prevented that people from out of the region will be ruling everything? Who has the power and willingness to change, and what do these people want to achieve? Can we learn from other areas where changes were occurring at a similar high rate?

The discussions about such questions with our expedition members and locals – and the fact that we are completely closed off from the outer world, because we have no phone connection or internet – keep me pondering…

- January 21, 2020

- Machiel Lamers

Tourism on Arborek

I am standing on our ship, gazing at a small dot of green in the middle of a blue ocean. As the dot becomes bigger and the details become clear, our curiosity grows. We have arrived at Arborek, a small island of 0.1 square kilometre (including a football field) with a population of 300 people, that has almost completely adopted tourism.

On arriving at the colourfully painted jetty we are greeted with cheers and smiles from the children playing in the lagoon. A welcoming committee invites us to sign the guest book. I quickly try to obtain some more facts: Tourism started in 2009 when Conservation International tried to convince the community to stop fishing in the Marine Protected Area surrounding the island and develop tourism as an alternative source of livelihood. The island now has 13 homestays (guesthouses) and 70% of the population has shifted from fishing to tourism.

Community-based tourism

The streets of the village all look freshly swept; very uncommon in these parts of Indonesia. Everywhere we see images of manta rays. Next to Arborek lays Manta Sandy, a place where these magnificent sea creatures meet to be cleaned by small reef fish. Women are sitting in the shade braiding manta hats for the tourists.

Braided manta hat.

My sociological brain grinds. How is this possible? Why is everybody so happy with thousands of visitors walking through their streets and looking into their houses? My own research on community-based tourism, as well as hundreds of studies worldwide, are all about its challenges. Tourism typically leads to growing division in the community and a loss of social cohesion.

Island of hapiness?

As I roam the streets, guided by Wawan, one of our Indonesian colleagues, I am trying to find more clues. Is it the geography? It is of course a very small island, populated and manged by only two clans. Is it the manta’s that attract shiploads of tourists to make sure there is enough cake for everyone? Is it the visible influence of the church on the island?

The island now has 13 homestays.

We stumble into a Danish volunteer who emphasises the strong hospitable culture of the Papuans and their collective decision making. A homestay owner tells us that he is not in it for the money; his enterprise is a way to lead an easy life with his relatives. Completely zen. As we return to the ship I am still puzzled. Have we discovered the island of happiness? Have we seen 300 actors perform a new touristic masterpiece? A combination of both?

- January 20, 2020

- Erik Meesters & Ricardo Tapilatu

First dive Raja Ampat, Sorido

So finally, after three hot days in Waisai where we had discussions with local authorities, we got on the Temukira, a nice little wooden ship that we rented for our expedition. It felt good to be on the water, much cooler and after days of rain it was finally sunny. We sailed to Cape Kri, where we anchored in the sand. The owner of Papua Diving, a diving resort, had invited us to have a look close to his property where apparently big changes were taking place.

Diving in a sinkhole

Our team consisted of five divers to photograph the bottom community and fishes along a number of transect lines. It turned out that we were diving in a sinkhole. While outside of the sinkhole the current was very fast, inside the hole it was very peaceful.

The sinkhole in front of Sorido dive resort (picture by Iqbal Alaik).

Popular dive spotSorido is close to one of the most visited dive spots in Raja Ampat, Cape Kri. And that became soon visible. Within half an hour we were surrounded by six big dive ships, so called liveaboards. The number of divers per boat can easily be between 15-25. One can easily imagine that 150 divers at once on one spot is too much.

Our liveaboard surrounded by four other boats.

Algae mats

We found that the sinkhole is dominated by Padina algae. Thick mats cover the slope of the sinkhole. A couple of years ago we hardly saw any algae, while now they seemed to be everywhere. What could have caused this change? At night, back on the boat, we discussed this with the team.

Algae thrive on nutrients, for instance from human waste. We found out that many live-aboard boats don’t have holding tanks for the waste water. Given that they anchor just next to the sinkhole, their sewage may end up in there. Because the sinkhole is so sheltered, everything that ends up in it is not flushed away like in many other places in Raja Ampat. As the dive resort owner summarized it: “At some of the dive sites, our guests literally got sh*t dumped on their head.”

The algae may however also result from the overflow of septic tanks on land, especially when the bottom consists of carbonate rock which is very porous. Ultimately, the contents of these septic tanks will end up on the reef. Another possible cause could be run-off from land, which often follows land clearing. The input from organic material from the land can lead to bloom of algae and cyanobacteria.

In the future we hope to find out what caused the algae mats, so the coral will recover and divers will have all the more reason to come back.

- January 16, 2020

- Machiel Lamers

A great momentum

After a long trip we finally arrived in Waisai, Raja Ampat. Here, we wanted to sort the fins and snorkels and meet the most important stakeholders for our trip. Through a tropical monsoon we ran to the meeting: around the table that looked like a wedding cake were sitting about twenty West-Papuan governmental partners, conservation NGOs, managers of luxury resort and dive centers and homestay owners. Pak Syafri, the director of BLUD UPTD KKPD (the agency responsible for MPA regulations) welcomed us, and Lisa Becking introduced the Resilience of the Richest Reefs project in Indonesian, including our plans for the coming days on board the Temukira.

Plastic waste and nutrients

We were suprised how well the meeting was attended. It appeared that there is a general sense of concern among the stakeholders about the rapidly increasing numbers of tourists and the related population growth on the islands. People mentioned how that leads to more plastic waste and nutrients in the water affecting the corals.

Several participants reported about coral diseases, algae growth and invasions of crown of thorns seastars. Others called for stricter enforcement of the regulations. For example, there is a cap on liveaboards- these are traditional vessels accommodating dive tourists. Only 40 are allowed in the area but people at the meeting observed more than that. They mentioned divers without entrance permits and an increase in illegal fishing. The director of BLUD explained that not everything happening in the MPA is under his control and that there is a lack of funds for patrolling the 1.3 million hectares of marine protected area.

Aksie!

Most of the meeting took place in rapidly spoken Indonesian, so I had to judge the intensity of the conversation by reading expressions. We all felt that the meeting ended with great energy, resulting in a joint call for action: Implementasie! Aksie! It was clear that everyone present was concerned with recent changes in the area.

The director of BLUD invited all the participants to collaborate in tackling the issues. For instance, some of the resorts are already collecting and recycling plastic in the surrounding villages and on the beaches. Resorts and homestays could develop waste water gardens to reduce the nutrient outflow into the ocean. Decision makers should be informed about the environmental impacts of tourism development in the MPAs. We left with the urge to start our trip: clearly, our visit is timely and people are eager to hear about our findings in the future.

- January 14, 2020

- Lisa Becking

Resilient Reefs

Mostly when you hear about coral reefs in the news, it’s bad. Disease & death. Luckily there are a few bright spots in the world where the reefs are still quite healthy. One of those areas is Raja Ampat, Indonesia. In 2016 & 2017 there were global bleaching events, where worldwide great numbers of corals died as a result of increased water temperatures. The reefs of Raja Ampat proved resilient and the corals did not collapse.

Our question is why? What makes the coral reefs in this area so resilient and what can we learn from them for the conservation in other areas?

One of the reasons is that the reefs are in the epicenter of the world’s richest marine biodiversity. To give some context, almost 600 coral species have been identified in Raja Ampat, compare that with about 100-150 in the Caribbean. The area is home to two species of manta rays, numerous sharks and all kinds of wonderous creatures such as the flasher wrasse. There are hectares of luscious green mangroves and seagrass areas, and reefs in different depths.

Tourism

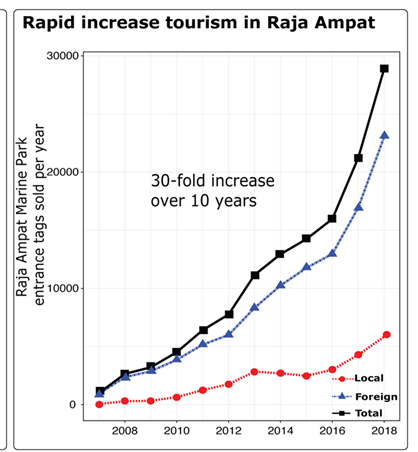

Simply put, the area is spectacularly stunning, both above the water and below. As such it is being highly promoted as a top tourist destination. I even saw advertisements for Raja Ampat in Centraal Station in Amsterdam a few years ago. The first time I went to the region in 2007, approximately 900 tourists visited per year. Since 2012 the access to the area has increased and so have the tourists, now more than 30.000 per year (see graph) and growing.

Number of entry permit tickets sold to domestic and international tourists

Tourism can stimulate the local economy, provide revenue for patrolling and conservation activities. However, if left unregulated, tourism can harm the reefs. For example, more tourists, mean more toilets, which mean more nutrients in the water if there is no proper sanitation. This can cause algae and bacteria to bloom in the reefs, as well as coral disease.

Expedition

With a diverse team of scientists, conservationists and policy makers we will conduct a reconnaissance trip of the area and a 10 day workshop on a boat. While most coral reef studies focus on pathways of degradation, we aim to beat the system to the punch and use our gained knowledge of interactions and dynamics of the local social-ecological system to identify pathways to build resilience against current threats such as climate change and increasing tourism.